Richard M. Christensen |

||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Failure Characterization

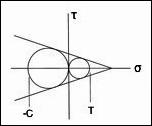

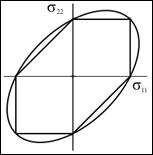

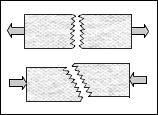

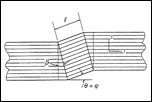

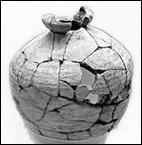

The illustration is of the quasi-static failure of cast iron under torsion. The failure surface is inclined at 45 degrees to the longitudinal axis. Thus the failure surface takes the orientation that produces the maximum possible tensile stress component (principal stress) as acting upon it. A failure criterion must respect and reflect this physical characteristic for this particular material type, but if it is to apply generally it must also be compatible with many other physical failure characteristics for other isotropic materials types. It is highly advisable that the failure characterization for any one materials type, epoxy polymers for example, follow directly as a specialization from a comprehensive form applicable to all homogeneous and isotropic materials. Success across the spectrum of all materials types, from very ductile to very brittle, would be much more likely to assure success for any one particular class of interest. In the present work it first will be required that the general characterization admit the one property Mises criterion at one extreme, since it gives the most nearly correct results for ductile metals. Then at the other end of the scale, realistic specializations must occur for the cases of brittle ceramics, glasses and geological materials, which surely would require more than one property. It is furthermore required that the general theory be calibrated by only a few (preferably two) failure properties. If many properties appeared to be needed, the situation would inevitably degenerate to being just that of adjusting or fitting parameters rather than that of an evaluation from mechanical properties. The same unsatisfactory situation would usually occur in merely fitting data for a single materials type with no regard for anything else. It is left as an exercise to show that the two property, general theory expounded in Section II predicts physical results for cast iron that are completely consistent with those described in the first paragraph above. On a scale going from limit case ductility to extreme brittleness, this example of cast iron corresponds to a moderately brittle case and thus is intermediate on that scale. Other examples from other major classes of materials are equally important to examine. The mainstream topics of traditional interest have mostly been composed of isotropic materials. However, anisotropic materials in general and fiber composite materials in particular are of great contemporary interest and relevance. These broader classes of materials will also be included. Beyond the idealization of quasi-static failure lie the even more difficult classes of fatigue and rate dependent failure. These too should be and will be covered. Nevertheless, the priority order taken here is that a consistent and self contained formulation of quasi-static, isotropic material failure must come first. If this most basic aspect of failure cannot be correctly treated, then there is little likelihood for succeeding with the even more difficult problems. Despite the historically slow and sometimes convoluted path of progress, modern developments for failure criteria have confronted the basic problems and yielded tractable and cohesive results. The main body of these failure criteria for homogeneous materials along with the complementary field of fracture mechanics go far toward providing a general framework for materials failure characterization. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recent Additons |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Key Junctures |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

General Matters |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Can Atomic/Nano Scale |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||

Copyright© 2019 |

||||||